GO WITH THE FLOW

By Hugh Davis

You might think the aircraft checklist has been around since the invention of the aircraft, but in researching this article I discovered that written checklists were developed just prior to WWII. However, I am thinking that when the Wright brothers gathered all the parts of their gliders and powered aircraft for that first flight, they may have made use of some sort of checklist.

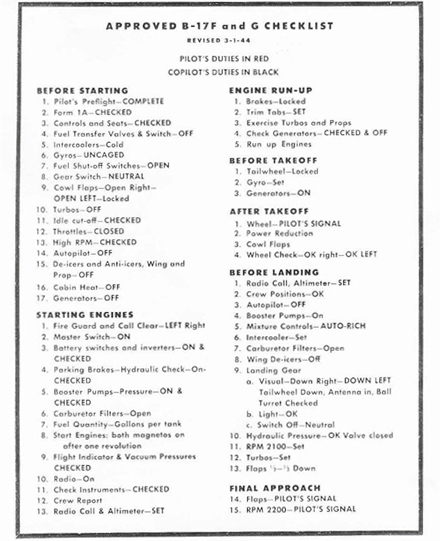

Back in 1935 the experimental Model 299 from Boeing was in competition for a government contract with two other aircraft. On October 30 Army Air Corps test pilot Major Plover Hill and Boeing veteran test pilot Les Tower took the Model 299 on a government evaluation test flight. But the crew forgot to disengage the gust lock. After takeoff, the aircraft entered a steep climb, stalled, nosed over and crashed, killing Hill (whom Hill Air Force Base was subsequently named after) and Tower. Other crew members survived with injuries.

Many commented after the crash that the airplane was too complex for its time, and even with two pilots some safety issues should be addressed. Boeing engineers and other test pilots used what we now call CRM to brainstorm a solution and hopefully save the company. They came up with a checklist that covered all critical phases of flight. Boeing lost that contract, but a loophole later led to a contract for 13 aircraft. With WWII in sight, we all know the rest of the story--the Model 299 became the B-17.

On my first flight as a pilot I can remember my flight instructor walking around the aircraft with a checklist in hand completing the preflight inspection. The checklist went on to cover every phase of flight from before engine start all the way to parking. Even today, if you forget to use the checklist on a check ride you can assume that a pink slip is coming!

But as much as the checklist has been a part of our flying since our first flight lesson, the National Transportation Safety Board frequently mentions failure to use a checklist as a contributing factor in an accident. Studies done with observers sitting in airline cockpits determined that many crews used the checklist as prescribed in their company's operations manual, while other crews never used it at all. Still others would respond to the challenge but did not complete the action. An example would be the MD-80 that crashed after departing Detroit, Michigan. Before takeoff the flight crew pulled an audio warning circuit breaker, then read the checklist but did not visually verify that the flaps were not deployed. The aircraft stalled on takeoff and crashed, killing all but one passenger.

During my tenure as a simulator instructor I witnessed many of the above traits whether working with a single pilot or a two-pilot crew. When a checklist was used, I often would see an enormous amount of time spent completing the checklist instead of going with a systematic flow. So I reverted back to my airline flying days and proposed to the program manager that I teach the "flow concept." It saves quite a bit of time, covers all the typical checklist items, and in a simulator training scenario allows the instructor to complete more tasks.

Here is how the flow concept works outside of the cockpit: You have received a call to stop at the grocery store to pick up some items for the next few meals at home. With a list in hand, you enter the store and start trekking the aisles using your own flow pattern. You might go left while others might go right, and pick up the necessary items. Your list might not make sense but your flow sure does. Standing in line at the checkout you go over the list to make sure that all items have been placed in the basket. Checklist complete and you are ready to "fly" home.

In the 690B Twin Commander, my flow begins by ensuring that all the switches are in the proper position for engine start. I begin with the overhead switches, flowing left to right and making a U-turn on the bottom row of overhead switches. Then, drop down to the pressurization panel on the lower left and across to the throttle quadrant and the circuit breakers to complete the flow. I use the same flow-through for all events--before engine start, after engine start, before takeoff, and before landing.

The only flow that I do differently is the engine shutdown. For that I start with the environmental panel at lower left, then go up to the overhead switches. I move right to left, ensuring that the radios, anti-ice, and generators are off. The last step is rotating the engine control switches to the Off position. One more optional step is to place the HP limiter switches in the Off position after engine shutdown so that I am ready for the next engine start.

For many years I have followed up "the flow" with the blue checklist you can find in most any Commander. As a Part 91 operation you can create your own. The FAA states that a checklist must include Before Start, Before Takeoff, Cruise, Before Landing, After Landing, Stopping Engines, and Emergencies. Using my airline flying background, I have created one that places all the needed checks on both sides of one 8.5 X 11-inch sheet of card stock or laminated paper. I fold it in the middle and stick it in the corner of the glareshield for quick and easy access. It is an abbreviated checklist that is more suitable for the experienced Commander pilot.

Going with the flow will smoothly lead you from the preflight to engine shutdown. Following it up with the written word (the checklist) will ensure that you have not left anything out of the shopping basket.

Happy flying!

Hugh Davis has been in the aircraft training environment for 40 years. A former flight simulator instructor and training center evaluator, he currently serves as a mentor pilot and managing pilot flying a Commander 690B. You can contact him at [email protected]

Discuss this article in the forums...